I’m currently working with the Waking the Feminists research committee on a count on the representation of women on the Irish stage in the last ten years. But I’ve discovered some of the questions we’re asking are age-old quandaries:

Question: Is a female collaborator on a script 1 playwright, or .5 of a playwright.

Answer: We’re counting it as 1 playwright, although this means the number of plays will be out of synch with the number of writers.

Question: When is a dramatic script by a woman not a play?

Answer: For some, when it’s a dramatic monologue performed for children. (See the instance of Ali White.)

Question: Is an adaptation of a novel for the stage a play?

Answer: ???

Question: And when does it cease to be her property?

Answer: Hmmm…

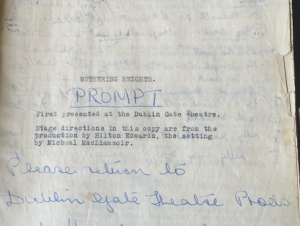

The US Library of Congress Catalogue of Copyright Entries, Dramatic Compositions Section, holds an entry for the 1934 adaptation of Wuthering Heights by Ria Mooney and Donald Stauffer. The entry records that Donald (a Shakespearean actor who would become a noted Princeton Scholar) was living in New York and Ria in Dublin, but publically records their joint ownership of the script, which brought to the stage Emily Bronte’s 1847 novel.

I found that entry some time ago, and it felt such a poignant record of the hard work and passion that went into the script, which appeared to be irretrievably lost.

I kept it on my computer, like a talisman, hoping it would attract the script to it. But it wasn’t to be found: Not in Ria Mooney’s collected papers in the National Library; not in the Gate Theatre archives in North Western University, in Gate papers in the Dublin City Archives, in the Gate Theatre archive now in Galway. But then I tracked it down… Location still classified information.

Why would she have copyrighted it in this fashion if she didn’t want the script to endure? And have we now let her down?

I found it filed under a different name, under the year of its revival (1944), in an incredibly delicate state (the stage manager’s copy) and crying out to be transcribed before it disintegrated into nothing. I took out my white gloves and even then felt reluctant to turn the pages, peeling tissue from tissue, as if dealing with the most tender of skin. Writers often talk about slitting veins, but confronted with a script as fragile as this, I realised it can be more about shedding layers of tissue and skin. As the script expands, the writer must become more delicate and sensitive. And in a way that’s what it was: Mooney poured so much of herself into the writing and playing of the script that the rehearsal process became an emotional trial.

When the Civic Repertory Theatre Company suddenly closed in New York, leaving Ria (and many others) out of work, she set to work with Donald Stauffer. Her copy of the novel of Wuthering Heights, full of handwritten notes and marks, is in her collection of books at the National Library.

I trawled through the manuscript, desperate to find some personal connection between Ria and Bronte, or Catherine Earnshaw: What did she find in this story? What drew her to it? Why was it the only story she ever adapted? I can’t answer definitively; I can only put forward my own thoughts.

When the teenage Bronte sisters, Charlotte and Emily, arrived at boarding school, it was noted that the girls didn’t know how to play, and that they spoke with a strong Irish (Ulster) accent. But there was more to the connection between the overly-serious Ria and the Bronte sisters than this.

I have long divided the world between Jane Austen people and Bronte people. They are distinctly different artists, with radically diverging temperaments and outlook on the world. Fans of Jane Austen are drawn to style, intellectual wit and are ever concerned with public appearance: what Q.D. Leavis calls Austen’s ‘surface delineation of life’. Bronte people dislike tales of manners and morals: they are sensitive creatures, more attuned to the messiness of emotional life. (If I’d applied this logic to my love life in the past, I’d have saved myself a lot of trouble.)

In 1847, just after the publication of Jane Eyre, Charlotte Bronte was advised to read the work of Jane Austen. Bronte politely retorted that she didn’t think Austen was a novelist at all: her work lacked poetry. It was ‘only shrewd and observant’; it was ‘a highly-cultivated garden but no open country.’

Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights is most definitely ‘open country’, and the woman at its centre is not in any way an idealised heroine. Catherine Earnshaw is an active contributor to life and her own fate. She is impetuous, passionate, wild and wilful. She recognises social proprieties but her marriage and attempt to meet traditional expectations ultimately kills her and leaves her restless soul haunting the moors. Was Ria’s adaptation prepared for strident feminist Eva Le Gallienne? Perhaps. In any case, here was a woman Ria could identify with.

It is no surprise to me that while the morality tales of Teresa Deevy were being staged at the Abbey, teaching women about repression and subjection to men, Mooney was presenting to MacLiammoir and Hilton Edwards the classical tale of the development of a young girl, devoid of support or emotional guidance, into a selfish and determined woman. (The rehearsal process, fraught as it was, deserves a separate blog post and I’ll do that next week.)

Wuthering Heights was (as far as we know) the only writing for stage that Ria Mooney did, but according to the Gate directors, when compared to the later Hollywood film:

Ria Mooney had preserved the essence of Emily Bronte’s mind into the few feet of the Gate theatre with greater surety than the celluloid had found in all those acres of Californian mountains. (All for Hecuba 167)

Mooney did more than adapt Emily Bronte’s novel, she captured and transmitted her spirit. She wrote and played a woman with passion, desire and a mind of her own. Does that make it a play? To my mind, it makes it a very important play in 1934.

Virginia Woolf wrote of Wuthering Heights:

[Emily Bronte] could free life from its dependence on facts; with a few touches indicate the spirit of a face so that it needs no body; by speaking of the moor make the wind blow and the thunder roar.

As we diligently work away, counting the number of male and female parts, the number of male and female playwrights and directors in theatres over the last ten years, I am forever aware that the depiction of women is so much more than numbers. Facts are useful, but life also exists independent of them.

If you’re one of the playwrights being staged this year, please bear that in mind. What spirit are you transmitting? What essence of Irish women are you filling the theatre with?

If you’re not a playwright being staged, you can still help with #WTFCount – Please do get involved! Next time you’re at the theatre: Count the number of men and women involved in the production (cast and crew). Many women have been doing this secretly for years, but now we want you to share this information.

Simply take a photo of the programme and post it on social media with your count. If you use Twitter, add the hashtag: #WTFCount

Yes, there’s much more to this than numbers. But numbers do count, so count ’em.

July 11, 2016 at 8:49 am

I wanted to cry when I read this. All that talent and hard work and genius so woefully under appreciated. Great detective work, Ciara!!!

July 11, 2016 at 8:57 am

Thanks Finola, had lovely chat with Sile this week! Hope you’re all well and delighted that Sarah is flying the flag for the Finlay women in Irish theatre. Cx