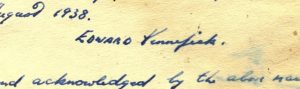

As I worked through the production files in the Abbey Theatre archives for Elizabeth Connor’s 1940 play Mount Prospect, I found a fragile and hand-written copy of The Last Will and Testament of Edward Kennefick. The other ‘legal papers’ were a nonsense, but this gave me pause: the elaborate lettering of the legal clauses, the blue ink, the length and density of text. Was this an actual will, somehow subsumed into the papers?

I know I should know better by now, but I still get caught out.

The only curious thing about this Will was that the signature is in block capitals. I realised this was definitely a prop; the odd punctuation and block capitals perhaps a hint to get the actor to pace his delivery of the words. I started to think about the designer, or possibly the stage manager, taking time after rehearsals to sit down and write this out. In the paint room at the top of the Abbey, or a backstage corner, a bowed head, testing paper and ink, mimicking the phrasing of a solicitor.

How many such letters are crafted to aid the imaginations of actors?

And then, what’s actually written in the letters so often opened, sent, or wept over on stage? Today, we often see text messages projected overhead, but letters are only visible to the performers. I know I’ve been frustrated by seeing actors handed letters they don’t actually read before reacting, or watching them tear up over something that’s clearly a ripped page of a script, but am I entitled to be? Shouldn’t I be watching the reaction, not the note?

In an interview on the podcast Theater People, new American star Philippa Soo talked about holding in her hands the letters Alexander Hamilton had shared with his wife Eliza in 1804. (I’m hoping the hit musical Hamilton about the immigrant founding father of America needs no introduction.)

As they rehearsed her song Burn, Soo asked for the actual words written by Hamilton to be reprinted on the prop letters she uses each night on stage. She didn’t want the script (or song lyrics), or a picture of the archived letter; she wanted the typed words. Adieu… Best of wives and best of women.

Somehow the words of the letter became central to the actress’s performance.

This is a very particular case. And as I can’t talk more about this with Philippa Soo, I conducted my own research with some gracious Irish directors.

Aoife Spillane-Hinks of Then This Theatre told me that she always prefers for the contents of the letter as dictated in the play to be written out. She said, ‘It would definitely look like a full letter, so if only part of the text of the letter is given in the play, I love it when the Stage Manager or Props Master makes up the rest of the letter in an appropriate fashion.’ Another creative task for which stage management receive little credit?

Theatre and opera director Tom Creed told me that if it’s a letter from another character in the play, he will ask the actor playing the sender to write it as part of rehearsal. (I can see the actor in the corner of the rehearsal room, chewing on a pen, cursing Tom for the extra homework.) Creed also insists on a real letter, rather than something random, ‘so the actor can read and react to it in real time and not have to waste energy imagining it’. This idea hit on the central point I was trying to understand: the imagination of the actor and their material reality somehow come together most strikingly in these slight objects that they hold in their hands

Actor and director Joan Sheehy shared with me that as productions run on, she’s known stage management to use a letter delivered on stage as a running joke: varying the text to keep the performer on their toes or amused.

She said, ‘As you can imagine it completely depends on the mood of the company and the style of the play but it can lead to great fun and anticipation as you open the page.’ As an actor she has been presented with letters that are a deliberate scrawl, which she says is ‘fine but it wouldn’t be my choice’. Sheehy emphasizes how particular she is as a director about the paper of the letter, ‘that it truly reflects the time and the provenance of the letter … and the worst is the same ’oul crumpled prop letter appearing every night!’

Again, this is insightful because the paper (rather than the text on it) is both what the audience sees and what the actor feels in their hand. It connects to both these senses: nothing to do with the text it contents. But should it?

Tony-award-winning Garry Hynes, Artistic Director of Druid, gave me a fantastic, pragmatic response to my question about letters on stage: ‘Why wouldn’t it be real?’ She couldn’t countenance anything else. In a theatre like Druid’s Mick Lally in Galway, the page is going to be clearly visible to the audience. She said, ‘If the actor is required to react in a real way to the contents of the letter than it makes sense that the prop itself be real.’

The insistence on ‘real’ is the tricky bit: these aren’t ‘real’ people, or ‘real’ rooms with walls. So why do we demand the fully authenticated article to prompt emotions that are essentially imagined?

At the core of much of Ria Mooney’s teaching at the 14th Street Theatre in New York was another letter. This one was a drill, a muscle exercise, she used for her young charges in the Civic Repertory Theatre. As the apprentice crossed the stage, letter in hand, Ria, from her place in the auditorium, called out the character type they were to represent: princess, pauper, pensioner. In that short distance, and with that simple gesture, they had somehow to convey it all. The biggest problem, according to accounts, was that there were frequently explosions from the subway work down the street that caused all kinds of unplanned facial responses. The irritating thing about this anecdote is that nobody says if they held an actual letter, real or invented, or if that was also part of the imaginative process.

Ria Mooney often tried to tease out the magical balance between imagination and ‘circumstances’. She gave frequent hints that she believed fully in the actor developing their imaginative senses. Instead of the warmed Chianti served by Le Gallienne on stage, she prized the intoxicating red lemonade supped on the Abbey stage. She believed in giving young actors ‘wrong behaviours’ when she directed, on the basis they had to work their imagination harder to present the character. As Mrs Kennefick, she summoned grief from her imagination and memory, but then simply read out the words written before her in the will. We ask actors to imagine their response, but then we give them the words to feed off.

As anyone who watched the clip of Warren Beatty presenting the Oscar this week knows, the real words can have a devastating impact.

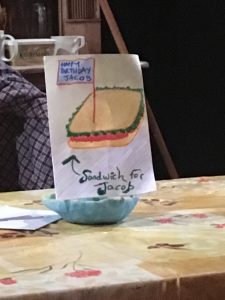

At a production in The New Theatre a few weeks ago, the final scene centred on the birthday party of young Jacob. After the curtain call, I crept down to the stage and took a picture of the birthday card on the table. I wanted to see it more closely, to know what was inside. The hand-drawn card, I discovered, was the work of playwright Michael Marshall. In fact, all of the cast members had drawn cards, which were swapped throughout the run. The time, effort and thought put into this paper somehow raised it above the status of prop.

But that’s perhaps how all these letters attain such powerful status. They are more than a mundane object simply because of the effort put in by the designer or stage management team. They are an artefact of the many people believing in the process, attending to the practical details that set up the magic and feed into the imaginative fiction of the actor.

I hope those birthday cards, and all the letters, get archived.

February 28, 2017 at 3:53 pm

Thoroughly enjoyed this article. My experience with paper props has also been as varied. The type of creation of ” being” seems to effect its accuracy. The acting approach be it method , improv, or pure inspirational guides me to what it is.Some singers want the grounding the paper props gives for them in a scene. Others have enjoyed playful, anticipation of what ‘s new. Personally, I love the details that can be found in forensic propping and the thrill of forging a document that can take a beating and effect a heart beat.

February 28, 2017 at 5:21 pm

Thanks for the contribution, Megan. C x