This month I’ve been thinking about going away with the fairies, and not only because of my post-Yale depression and the inauguration of the new US President. (I’m not going to name him.)

I’ve been thinking about the phrase ‘away with the fairies’, so often used in Ireland as a suggestion that somebody has slipped from reality and is experiencing mental unrest, or ‘having an episode’, to use the modern parlance. To go ‘doolally’, to give you some trivia, is from the British Army sanitorium in Deolali, India, where soldiers struggling with mental health issues were sent during World War II. But Irish people didn’t go to India, they went to visit the little folk.

And how does this connect to Irish actresses?

In December 1928, the Civic Repertory Theatre Company sold 399 orchestra seats and 42 boxes for the performance of Peter Pan, with Eva Le Gallienne in the starring role. It was their largest box-office take to date. The rest of the year in the Fourteenth Street Theatre in New York was highbrow Russian drama and American classics, but at Christmas, Le Gallienne brought the same artistic vision and rigorous discipline to the J. M. Barrie children’s story about a young boy who can fly and will never grow up.

After acquiring the rights, Le Gallienne (professional to the last) asked for the blessing of Maude Adams, the first actress to play Peter Pan on Broadway in 1906. The notoriously shy and polite Maude gave it quietly. This actress always presented herself as virtuous and solitary to her public; she was another star afraid to bring attention to her personal life. She was lesbian, and had two long-term relationships with women. (She also became a pioneer in stage lighting, but that’s another blog post.)

Le Gallienne may, or may not, have known this at the time they met, but both she and Maude were to be part of a long tradition of lesbian performers who presented themselves as the boy who wouldn’t grow up.

It’s believed that Peter Pan was originally played on the stage by a woman because casting a young boy would bring all kinds of labour law/union problems. But androgynous and athletic, a mischievous imp, the character of Peter has an exotic mix of characteristics traditionally neither male nor female. In her fascinating study of the physicality of Mary Martin (another lesbian performer) playing Peter Pan, Stacy Wolf says, ‘For a boy, Martin looks like a woman; for a woman, Martin looks like a boy.’[1] Sexuality simply doesn’t matter; Peter is a role model to both boys and girls.

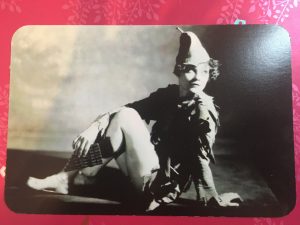

Maude Adams’ Peter was feminine, wearing russet-coloured tights with garters, frills on her shoulders and the wide neckline still known today as the ‘peter-pan collar’. Le Gallienne was more androgynous: a faded-blue tunic, only just long enough to cover the flying harness, and a bluebell-shaped cap. She abandoned tights, covering her shapely legs and feet only with dark, tanned makeup, to the shock of some theatre critics.

Ria Mooney was there that December in 1928 when it was first staged, although she wasn’t in the cast list. She had appeared in L’Invitation Au Voyage a week prior, when the box-office take was about a quarter of the receipts that week. She may have missed spending Christmas with her family, but there was theatre to occupy her…

I can see her, creeping into the back of the thronged auditorium, hoping to find a seat to watch the final act. The pirates’ costumes include twelve-inch heels, so that they tower above Peter, with his blue-bell hat, and his friends. As a climax, Eva steps off the stage and into the air, soaring across the air to the first balcony. Ria holds her breath. The children are roaring support, clambering on the seats and reaching upwards. If even one arm reaches her, it could unbalance the rudimentary harness and cause a serious accident. But Eva shows no such fear and she lands effortlessly, to roars and stamping feet. It took Le Gallienne a few moments to realise the children didn’t know applause; they voiced their approval.

There’s a rich tradition of lesbian women playing Peter Pan in both England and America, but as I read more into this, I wonder: why aren’t there Irish women who’ve played this part?

The Irish Playography website gives only one original production of the story, a version translated into Irish and performed at An Taidhbhearc in Galway in 1987. This is an intriguing detail: Peter was played by a lady but Irish folklore treats ‘the little people’ very differently to the Americans. Going away with the fairies has very particular connotations that are not to do with mischievous imps, games and flying; they’re a malevolent and dangerous force, with a very particular set of ethics and harsh sanctions of any perceived transgressions.

And of course, Ria sets out her connection with this fairy tradition right from the opening line of her autobiography. Born on the last day of April, Ria describes herself as a changeling: an ugly and sinister creature left by the fairies in place of her parents’ real (and conventional) child on the eve of the Celtic feast, Bealtaine. Ria always felt different; she had desires and ambitions, and an accent she herself described as ‘affected’, that weren’t common to Irish women of her generation. She was ‘of the fairies’ and that wasn’t something for her, or her family, to be proud of.

Yeats and Lady Gregory played a part in sustaining these Celtic myths, albeit in an innocent, charming way. A twenty-one-year-old Aideen, on being interviewed by a New York newspaper in the 1930s, played up to the stereotypes by describing seeing a leprechaun while gathering cotton in Connemara. (I don’t believe a word of it.) Aideen was described as a child of the Irish Celtic twilight, but the journalists obviously didn’t understand the connotations to that.

The most famous example of ‘being away with the fairies’ is Bridget Cleary. She was a Tipperary woman, childless, financially independent and fashionable from her work as a seamstress, and rumoured to be having a sexual affair outside her marriage. Her husband and other villagers burned her to death in 1895, claiming the fairies had taken the ‘real’ woman and left a dangerous spirit in her place. Cleary has been called ‘the last witch in Ireland’, but that wasn’t a phrase ever used at the time by Irish people: we don’t have any tradition of witches.

A woman having a voice and economic power, expressing yourself and your desires, in Ireland is equated with being a dangerous, malevolent spirit from another world. Is it really any wonder we don’t have a tradition of Peter Pans?

But we’re not away with the fairies; we’re right here: calm, dignified and demanding to be heard.

And if we decide to do away with tights and colour our legs with make-up, then that’s our own business. Personally, I’d recommend the Sally Hansen product for tanning your legs.

As we race towards the deadline for publishing the data on the Waking the Feminists study, there are times when equality of representation for women on the Irish stage seems like a Never-Never Land, but I do hope to see an Irish Peter Pan here some day.

[1] Wolf, S. E. “”Never Gonna Be a Man/ Catch Me if You Can/ I Won’t Grow Up”: A Lesbian Account of Mary Martin as Peter Pan.” Theatre Journal, vol. 49 no. 4, 1997, pp. 493-509. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/tj.1997.0119.

January 29, 2017 at 9:14 pm

Post-Yale depression? Oh no!

Love the description of Ria watching that flight through the theatre.

January 29, 2017 at 9:21 pm

Thanks Finola! Lovely to hear from you – Hope you and Robert are well.